Searching for the invisible: Georgia Southern student wins big for nondestructive testing application

Every day, 40,000 cars cross the I-40 Hernando DeSoto bridge between Memphis, Tennessee, and Arkansas. The bridge, built in 1973, is made of corrugated metal and twisted steel, towering above the muddy banks of the Mississippi River.

In 2021, a worker with the Arkansas Department of Transportation discovered a major crack in one of the steel support beams during an inspection. The fracture was so severe that the bridge was closed for three months for emergency repairs, costing approximately $10 million.

Georgia Southern University manufacturing engineering student Chowdhury Irtiza says he followed the news closely.

“The Department of Transportation found that they’d made a repair before to fix the problem,” he explained. “But that repair didn’t take properly because they failed to detect another internal crack.”

Irtiza says it’s difficult to find these cracks because of the bridge’s structural nature.

“This is a very big, very massive structure,” he said. “You cannot slice every single part and see if a defect exists. To do that, you need to use nondestructive testing.”

This is usually done with ultrasound technology. Engineers send out a high-frequency sound wave that produces an echo when it hits a crack. That echo generates information for the engineer to interpret and assess the structure’s condition.

But Irtiza has found a way to produce even more accurate, detailed reports.

“Cracks are difficult to detect with conventional ultrasound testing,” explained Irtiza. “That’s why we use the total focusing method.”

Total focusing is an enhanced technique for collecting the maximum amount of raw echo data possible to produce an accurate simulation.

“By combining simulations with the total focusing method, we’re able to produce inspections that yield a 15% increase in crack signal detection in comparison to standard conventional methods,” he said.

This major quality improvement gives engineers a more detailed understanding of the bridge, giving all drivers the chance for a safe commute. Irtiza says it’s all about finding the right frequency.

“You have to find the optimal frequency to get the best image of the defect,” he said. “This helps save time and money, because you can’t just do trial and error to figure that out. I know that from experience.”

His experience came from a deep love for engineering, which took him from Bangladesh all the way to Statesboro.

“I didn’t know a lot about ultrasound or how it worked before coming here,” said Irtiza. “I was already working as a casting engineer, but I was fascinated at the thought of using ultrasound to tweak the material properties of the materials I worked on.”

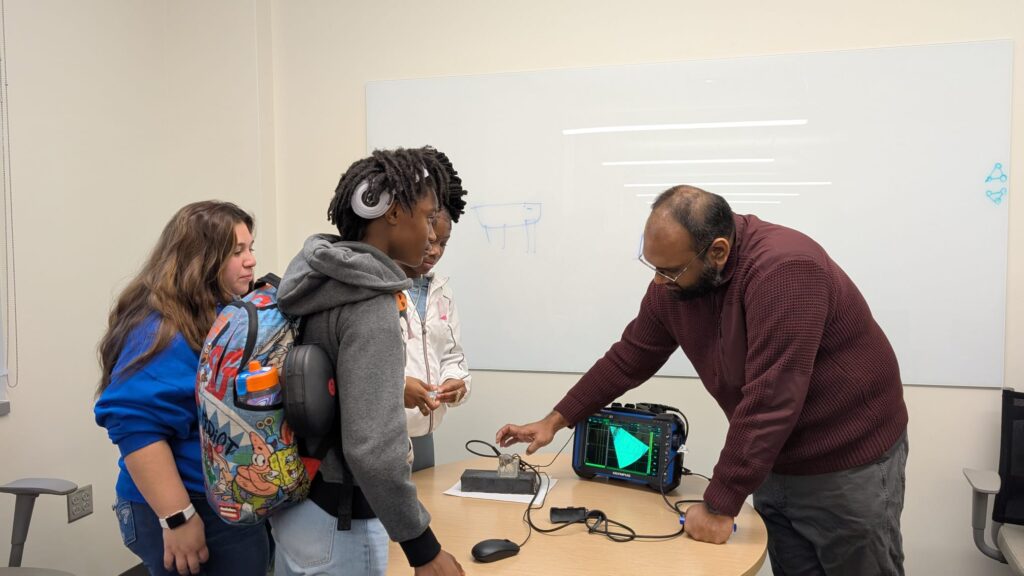

That’s how he met his mentor, Georgia Southern manufacturing engineering Associate Professor Hossein Taheri, Ph.D., working in the Allen E. Paulson College of Engineering and Computing. Their first emails quickly led to a close working relationship, with Taheri offering Irtiza the chance to come to Statesboro to assist his research.

“Dr. Taheri is one of the pioneers of this method of ultrasound testing,” Irtiza explained. “The work he’s doing is really incredible.”

Their working relationship became an important one to Irtiza.

“I’m actually very grateful to have him as a mentor,” he said. “I’ve heard a lot of scary things from my friends at other universities. Their professors are really strict and not very approachable. But Dr. Taheri has always encouraged students to share their thoughts and questions.”

Irtiza credits this relationship as a source of inspiration when it came to taking his ultrasound research from the lab to the convention floor — specifically, the poster competition at the International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition in Memphis.

“There were a lot of Ph.D. students from very big universities,” said Irtiza. “Their papers had multiple authors, and they came from big research groups. I was definitely wondering if my work would be recognized.”

He says it didn’t initially register when he heard his name called as the winner of the best research award.

“I couldn’t understand the emotions that hit when they announced my name,” he explained. “But then I found my professor and told him. And he was so happy for me, and that’s when I realized what I had done. It was a major accomplishment, and it felt good.”

Irtiza plans to continue his time at Georgia Southern by pursuing his doctorate in engineering.

“The research I’m doing is actively making an impact in the field of nondestructive testing,” he said. “I’m able to do that because of the investments Georgia Southern is making in the field of research. It’s inspired me to make more investments in myself and my career as well.”